imitation shaped brick tiles have the exposed face generally made to brick dimensions to give the appearance of brickwork. To fix them to a timber-framed structure one of two methods was employed, depending on the type of backing. Where the infilling was of wattle-and-daub, the usual practice was to cover the entire building with horizontal softwood boards onto which the tiles were nailed and bedded in lime putty. Where the infilling was brick nogging, the boards could be omitted and the tiles were bedded onto the face of the wall with plenty of lime putty and secured in addition, where possible, with nails. These tiles could also be fixed to battens nailed to the face of the walls, but this is much less common than was originally thought. In addition to being bedded, they were also pointed in mortar, so preserving the illusion of brickwork. The tiles were made in both headers and stretchers – although it was common to use headers only, as can be

seen in many of the houses in Lewes and, for instance, on the rear elevation of Guildford House, High Street, Guildford, Surrey.

When well constructed, these mathematical tiles are practically indistinguishable from the true brickwork they intend to resemble. This illusion is often dispelled, however, for frequently their use was restricted to the main elevation, with the side and rear walls covered with tiles or other cladding material, often finished with only a vertical batten at the corners. Corners were always a problem, it seems, and Nathaniel Lloyd in his A History of English Brickwork mentions the use of rusticated timber blocks painted to represent stone quoins at the external angles. Special corner bricks were not made until the end of the 1700s and were rarely used, being more common in Surrey than in Kent and Sussex. Other ‘tell-tale’ features are the lack of arches over the windows, the widespread use of header bond, and the setting of the window frames flush with the wall and lined with a thin timber batten like the corners.

Although generally restricted to the front elevation there are rare examples of these tiles being used on side elevations as well; however, there appears to be only one example in which all four facades are clad, and that is Spring House, Ewell, Surrey, built about 1730, where not only all three floors of this timber-framed house were clad but also the parapet as well.

Exactly when these tiles were introduced is unknown, but it is evident that they appeared before the introduction of the Brick Tax in 1784, the avoidance of which is often suggested as the reason for their popularity in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Recent research, however, has shown that these tiles were taxed as well as bricks from the commencement, although the tax on bricks was increased twice after 1794 while that on mathematical tiles remained unchanged. Moreover, the tax on tiles ceased in 1833, while on bricks it continued until 1850. One earlier example of their use is Helmingham Hall, Suffolk, when between 1745 and 1760 the old timber-framed building was modernized by the underbuilding of the first-floor jetties and by the battening out and hanging of mathematical tiles to the upper floor.

Although found on occasions elsewhere in the country, most are in the South-East, where there was a long tradition in the production of excellent tiles and bricks. However, why they never gained popularity elsewhere – for instance, in Essex and Suffolk, where bricks and tiles of equal quality were produced – has never been satisfactorily explained. Most are to be found in Kent and East Sussex, especially in the southern and coastal towns of these counties – Canterbury, Hythe, Tenterden, Lewes, Rye and Brighton – but they have been seen in Surrey and Suffolk and also in Hampshire, Wiltshire, Berkshire,

Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. Generally they are to be found in towns, rarely in rural areas.

Although usually these mathematical tiles were made of local clay and were therefore similar in texture and colour to local bricks, this was not always the case. Black tiles, often glazed (particularly around Brighton), were also manufactured. Sometimes two different colour tones were employed, as at Cotterlings, Ditchling, Sussex, where black tiles were used with red tile dressings. In some instances, however – and this is particularly true of the black-glazed mathematical tiles of Brighton – they were used to face an existing brickwall.

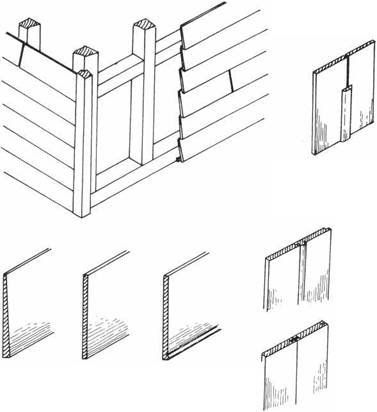

Weatherboarding, sometimes known by its American name of clap- boarding, is yet another method of cladding a timber-framed building to render it both water – and draught-proof (57). Its use in preference

|

|

|

feather-edged square-edged |

|

beaded-edged |

|

vertical boarding with rebated and beaded joint |

|

vertical boarding with tongued and grooved joint |

|

vertical boarding with butt edges covered with batten |