|

|

|

|

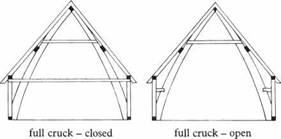

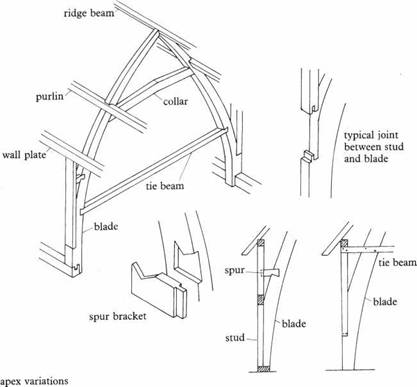

The characteristic feature of a cruck building is that the weight of the roof, and often that of the walls as well, is carried on a series of transverse trusses, each formed of two inclined timbers which rise from the ground and meet at the apex, tied together by a collar or tie-beam to form an A-frame (32). This frame then serves as a roof

|

|

|

|

truss to support the purlins and ridge-beam. Consequently the vertical walls have no structural importance, and when constructed of timber they depend greatly on the crucks for both support and stability.

The inclined timbers of the cruck frame, known as ‘blades’, were cut from trees which had, whenever possible, a natural curve, or from the trunk of one tree split in two along its length to ensure a symmetrical arch. The blades varied in shape according to the curvature of the tree and could be nearly straight, smoothly curved or elbowed. The ends of the blades were either supported on a stylobat or framed into a sill-beam. At the apex, however, a variety of methods were used to secure the blades, and N. W. Alcock in his book A Catalogue of Cruck Buildings gives distribution maps of the six main methods. The most common forms are not jointed at the apex but held together either by a yoke situated at the top on which the ridge-beam sits or, somewhat lower, by a collar with the blades butting against the ridge-beam. In other cases they are either simply butted, halved or crossed. Between each cruck frame ran the ridge-beams and purlins which supported the common rafters. When the external walls were of timber, the tie-beams were extended until their ends were directly above the base of the blades, and vertical posts were introduced, pegged to the base of the blades and to the end of the tie-beams. Wall-plates running between each cruck frame were fixed to the end of the tie-beams, and the panel between each post was filled in with studs and horizontal members. Often, however, in order to obtain more headroom the tie-beam was omitted, and in these cases the wall-plate and vertical post were tied back to the cruck by means of a ‘cruck-spur’.

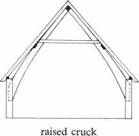

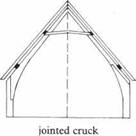

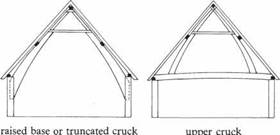

The above briefly describes the ‘true’ or ‘full’ cruck, but there are several other forms of cruck construction which, although not full crucks, are obviously related, some more than others, to the cruck family. First there is the ‘raised’ cruck which is similar to the full cruck in all respects except that, instead of starting at ground level, it starts some way up a solid wall; it has been defined by R. A. Cordingley as a truss in which the feet of the blades are raised at least five feet above ground level. In fact, full crucks are often referred to as raised crucks because the starting-point of the cruck, being concealed within the wall, is uncertain. With the ‘base’ cruck the blades, although rising from the ground, are truncated well below the apex and are tied together at the head with a tie-beam or collar which supports the roof structure. In the raised base or truncated cruck only the middle – the curved part of the cruck – is used, while in the ‘upper’ cruck the blades rise to the apex from a tie-beam at or near eaves level. Another form of cruck construction is the ‘jointed’ or ‘scarfed’ cruck where a vertical post is jointed to an inclined blade to obtain a cruck-like form (34).

|

|

|

|

|

halved housed |

|

yoke |

|

crossed |

33. Cruck construction

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

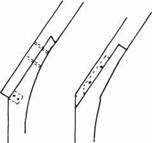

face-pegged continuous face-pegged with end mortice and

mortice and tenon tenon tenon