Strong visual impressions of laboratory spaces probably occur to many people who pass through the Wallace pedestrian street each day. From the overhead gantry crane to the candy-colored display of ducts and pipes, the components of this central space evoke a friendly workplace. For the students and scientists who work there, the central street is a core for the laboratory spaces and a communal forum.

Architectural clarity connects the cold Winnipeg climate, the prefabricated construction strategy, selection of systems, response to laboratory requirements, and the organization of spaces. The success of the design is inherent in the integration of these disparate aspects of the program into one guiding architectural concept.

Ron Keenberg generously contributed to portions of this case study.

|

C |

orporate headquarters and speculative office towers dominate our city skylines. Office space also spreads from the urban core into suburban office parks and the outer rings of regional mixed-use centers. As the industrialized world turned to service-based economies, corporate patronage played a parallel “skyscraping” role in architectural design activity.

The U. S. Energy Information Administration’s 1995 study, Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey, reveals the magnitude of office-building impact on the built environment. In number alone, office buildings in the United States rank second only to retail buildings and just ahead of warehouses. There were more than 700,000 office buildings in the United States in 1995. In terms of occupants, offices housed 35 percent of the commercial U. S. workforce, or some 27 million people. With the 10.5 billion ft2 of floor space these buildings comprise, the average office is only about 15,000 ft2 and holds some 40 workers, at an average 387 ft2 per occupant. Completing the statistics, 90 percent of office buildings are smaller than 25,000 ft2 and only 3 percent exceed 100,000 ft2. Finally, and amazingly enough when we consider the typical city skyline, only 1 percent of all U. S. office buildings (roughly 8,000 of them total) are more than ten floors in height.

Because of their dense occupancy patterns and intense use of equipment for producing work, these same offices (still taking the U. S. Energy Administration’s perspective)

|

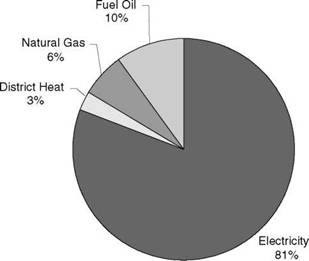

Figure 6.1 Annual site energy use in office buildings. |

are the single most intensive commercial energy users. Spending well over $15 billion per year in 1995 dollars, office energy averages more than $1.50 per ft2 per year.

|

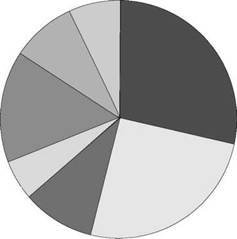

Other 7% |

|

Water Heating 9% |

|

Lighting 29% |

|

Equipment 16% |

|

Ventilation 5% |

|

Cooling 9% |

|

|

|

Figure 6.2 Annual cost of energy use in office buildings, $15.85 billion. (Data source: Energy Information Administration, 1995 Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey.) |

|

Space Heating 25% |

The real cost of business in an office building, however, is the working staff. A $60,000 per year employee occupying a 400 ft2 workspace costs an annual equivalent of $150 per ft2. This amount surpasses what the floor space cost to build and is more than ten times the annual ener

gy expense of fueling the office. Recognition of this proportion has led from the design of efficient office buildings that save energy to a more humanistic and profitable focus on productive office environments where comfort and health are the main priorities. It is easy to see that a small change in the design of a $120 per ft2 construction cost of an office building could have great impact on longterm business economics, even if it has only a small effect on worker productivity, absenteeism, or workforce recruitment and retention.

Critical relationships between occupant comfort, office productivity, and bottom line economics offer significant opportunities for design. Leveraging office environment resources to enhance occupant health, comfort, and well-being can import enormous value to effective architectural services. It is the role of architects, as the stalwart champion of what is human about good buildings, to serve these needs.

A number of other stimuli of change must also be considered. Management strategies like rightsizing, outsourcing, and total quality management (TQM) change the office dynamic. Information technology (IT), along with office automation, affects how work is produced and collaborated on. Worker productivity levels are finally beginning to reflect the vast improvements anticipated from use of computers. There is growing awareness of indoor air quality (IAQ), sick buildings, and personal control of environmental conditions. Ergonomics has become an everyday office science. The list goes on, but all these issues reflect the focus on productivity — and, consequently, the trend toward designing for human comfort factors.

From the systems perspective, then, offices present a specific set of challenges, best defined as energy, comfort, and flexibility. The first two of these, judicious use of energy and occupant comfort satisfaction, completely overlap. Efficient lighting means using light to its best and most comfortable effect. Daylighting saves energy and psychologically enhances the workspace. Passive envelope systems restore contact with the outdoors. Tight thermal control provides balanced air distribution and accurate control of comfort levels. Regulated mechanical ventilation and IAQ ensure a good environment.

The third challenge, flexibility, involves attention to two areas. First, personal workstations have to offer occupants a great deal of control. Repetitive motion injuries (like carpal tunnel syndrome) illustrate that no one is sufficiently “average” to fit satisfactorily into a desk made for some idealized model worker. Adjustable-position workstations also suggest adjustable lighting, air motion, and background sound levels.

The second area to be examined for flexibility is the office building itself. Modern offices must rearrange workspaces, re-form project teams, or even sublease floor space during business downturns. An adaptable infrastructure is needed for environmental services, communications, networking, and a general “plug-in” modular approach to interior systems from telephones to partitions.