|

|

Architectural intention, for the purpose of this discussion, is defined as the particular aspirations of the designer or

design team that lends a unique character or set of qualities to a building. The intention is usually a formative rule established early in design thinking. Based on a literal or symbolic interpretation of the problem, it takes the shape of a value statement about the essential nature of the design solution.

Karsten Harries, in his essay “Thoughts On a Non- Arbitrary Architecture” (1983), identifies several notions of how architectural intentions are founded. The philosophical foundations he discusses include the primitive but noble basis of shelter, the resolution of art and science, the ethical duty of providing a meaningful world order, and the goal of articulating beauty as an essence. Christian Norberg-Schultz writes of similar motivations in his book Intentions in Architecture (1965). These two works convey a sense of how critically acknowledged architecture is differentiated from the functional commodity of commonplace buildings. Successful architecture has historically come from individual assertions and the built manifestations of personal philosophies, not from standardized practices, geometric formulas, or stylistic fancy.

Authenticity implies that each designer must find and sincerely act upon his or her personal belief system. It is for time and culture to decide how appropriate the vision was to the problems addressed.

As a method of delving into the philosophical basis of architectural intention, consider some of the dualities with which architects deal and how individual ideas will result in a comfort level at some position between the two poles of the conversation. The most familiar of these discussions is of the paired determinants “form” versus “function.” Rather than seeing the two as opposing forces, where “form follows function” or vice versa, consider instead that they “dance together.” Imagine that this dance is a generative conversation in which an appropriate balance must be struck. It is from such conversations about the determinant forces of architectural solutions that unique, creative, and responsive resolutions arise.

These dualities, these generative conversations between poles are everywhere to be discussed in architectural thinking. Consider the following list, based loosely on Karsten Harries’s essay:

• The urge to beauty

• Oneness with nature

• To dwell (after Martin Heideger, 1949)

• Complexity of inclusive whole (after Robert Venturi, 1966)

• To create meaning from order

• To establish order from chaos

• To articulate a binding worldview

• To heal the rift between science and art

• To heal the rift between craft and industry

• Sustainability

• Distrust of technological solutions

• To express the view of an ideal way of life

Each of these items represents a philosophical position that can be thought of as a basis for architectural intention. Each is a generative issue from which arise design ambitions. And each item also represents a range of possible positions between two polar ends of the same notion. A considered system of beliefs will articulate the means of establishing a balance between these and doubtless other dualities. The significance of these operational beliefs clearly delineates the distinction between architectural accomplishment and commodity building.

It is clear from a historical perspective that significant examples of good architecture are not likely to result from whim, fancy, personal taste, or a bag of design tricks. Experience has proven that it is essential for architects to articulate a set of ideas that act as the binding glue and unifying agent for both their collective works and for individual buildings. This “binding glue” also acts as means by which, as Harries and Norberg-Schultz have shown, technology and design are integrated into architectural expression.

Intentions for individual buildings are often expressed as philosophical statements, geometric parti, or pattern – making rules of form. They serve an adductive purpose, a template for testing alternate possibilities for the design solution. This is the corollary to deductive reasoning that scientific thought uses to reduce possibilities through logical clues to correct answers. Unlike a scientific or engineering solution, architectural intention is not a rational deduction from the constraints as much as an empirical attempt to make design problems fit into a well-considered but idealized template.

Architectural intention cannot always be summed up in short, pithy sentences. This is naturally because good buildings are seldom composed of one simple idea. And intention is not always explicitly stated as an element of the design process. An analytical look at examples of widely recognized architecture, however, reveals strong organizing concepts with a basis in sound statements of value. It is these organizing concepts that express the architect’s interpretation of the essential design problem and thus form the intention.

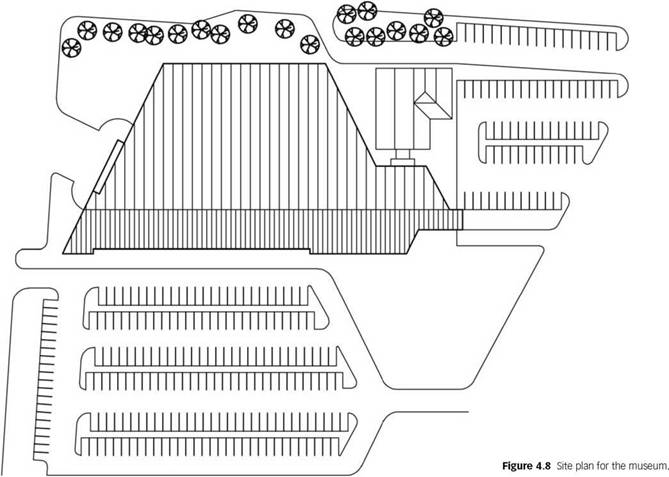

Intention must be distinguished from programmatic criteria. A fundamental failure is virtually ensured by confusing the goals of ambitious design intention with the checklist objectives of programmatic needs. Making the Pacific Museum of Flight a daylit museum, for example, only summarizes a programmatic decision and would be just one of several on a long list of design objectives. Ibsen Nelsen (1991) looked for the ambitious intention that would order his work on the museum. He sized up the PMF by touring other museums of flight around the country to gain a sense of precedent. He was disappointed to see most collections sitting in hangarlike buildings and displayed rather plainly. The guiding architectural intention that Nelsen finally used to formulate the design of the Gallery was “to display the airplanes as if they were in flight.”

Differentiating Critical Architecture from Commodity Building

In his book The Emerald City and Other Essays on the Architectural Imagination (1999), Daniel Willis describes the difference between lowly “labor” and meritorious “work.” Labor, he points out, exhibits an absence of human imagination and does not result in a product. Labor is best done by machines. Sufficiently enlightened work, meanwhile, becomes analogous to play. Poetic works, by Willis’s analogy, can be taken to be those products of endeavor that appeal to significant human experience by evoking imaginative response. This distinction is in close agreement with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s investigation into the imagination of especially creative people. In his book Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (1996), he interviewed 91 exceptional individuals collectively sharing 14 Nobel prizes, among countless other significant accomplishments. The common ground of their experience was what Csikszentmihalyi terms “flow.” The elements of this transcendent experience will be familiar to most readers: “Always knowing what needs to be done, a merging of action and awareness, intense focus without fear of failure, disappearance of self-consciousness, and a total distortion of time [sic].”

The description of this working flow as “transcendent” is a logical extension of the psychologist Abraham Maslow’s (1954) study of “peak experiences.” Maslow

|

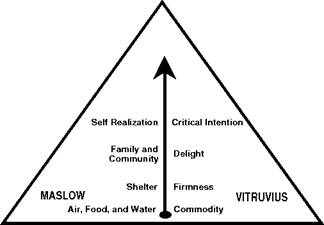

Figure 4.9 The Pyramids of Maslow and Vitruvius. |

believed that these nonordinary experiences were essential to “self-actualization.” With Karlfeid Graf Durckheim (1967), Maslow pioneered the term transpersonal psychology and outlined the parameters of transcendent experiences and the barriers to encountering them.

The link between architectural intention and “flow” leads, it is hoped, to poetic and “actualized” works of architecture. It is the portrayal of this personal transcendent experience that architects wish to convey in built environmental form. A simplification of this conveyance may use the Vitruvian maxim “Commodity, firmness, and delight” as a three-tiered pyramid of “architectural needs” (Figure 4.9). As in Maslow’s pyramid of human needs (1954), a building must first satisfy our basic requirements for safety, shelter, and space. Thereafter, its lasting qualities and endurance can be ensured. Then, we find refreshment for the human spirit in the delight of our surroundings. Finally, adding a layer to the Vitruvian maxim, the crowning tier of the architect’s pyramid is the nonordinary and transcendent aspect of critical architectural intention. Successful realization of inspired intention is what separates the splendor of architecture from the merely satisfactory buildings of everyday experience.

Formative Intentions as the Adductive Basis of Design

Because building design is such a large task influenced by so many factors, architects tend to think in adductive and synthetic rather than deductive and analytical terms. Adductive logic differs from inductive and deductive logic by starting with an idea and then testing it against the facts. In mathematics a theorem may be proven through adductive reasoning that begins with the statement of an equality and then produces transformations that give proof of an identity, like 1 = 1. Inductive reasoning, on the other hand, builds truths from observed facts, and deductive reasoning uses chains of logic to analytically reduce what is known to a final conclusion.

The very nature of their inherently integrative thinking means that architects seldom engage in design as an inductive or analytical process. Their approach is necessarily more inclusive, less mechanistic, and therefore more systems oriented than any linear procedures can describe. So unlike the deductive reasoning a scientist or engineer is classically believed to employ, architectural reasoning is better described as adductive. Analytical deductive processes work by optimizing single factors in isolation and constructing a whole from sound elements. Adductive, integrative thinking conceives the complex whole and explores the proper fit of different subunits into the superlative value or truth of the whole, the gestalt. This is part of what Christian Norberg-Schultz refers to in his definitive Intentions in Architecture (1965) as “the integration of the problem into a larger whole.” It is worth noting that many other disciplines are moving toward this holistic approach to the design of solutions for everything from agriculture to particle physics.

Somewhere in the architectural process of design, the activity moves from research and shaping of the building problem into a graphic organization of response. This diagram or parti (to use the Beaux-Arts root) seeks to give form to architectural intention and to engender a solution to the building program. The diagram is not itself the solution, but it does present a framework within which ideas will be tried for logical fit and compliance with design intention.