wall-frame often had strokes cut above the numerals, indicating which floor they related to – one stroke for the first floor, two strokes for the second and so on. In some cases, as at the Ancient High House, Stafford, Arabics were used. These identification marks enabled workmen to sort the timbers easily prior to erection.

The erecting of the timbers on site differed between those of box-frame and cruck construction. The method employed in cruck building was rearing; that is, the components of each frame, previously prepared in the carpenter’s yard, were jointed and pegged together to make a rigid frame which was then raised through ninety degrees, tenons on the bottom of the blades engaging with the mortices in the sill-beam. In addition, the longitudinal members – the wall-plate and purlins – were also used to locate each frame as it was raised. Although, according to L. F. Salzman in his book Building in England Down to 1540, there is evidence that for small buildings of box-frame construction a similar process was adopted (that is, that the end frames were assembled, pegged together and raised as a whole), in the majority of cases it appears that the building was erected timber by timber, the assembly proceeding in well-defined order, the joints being secured by oak pegs driven into the holes prepared in the yard and left slightly projecting. The hole in the outer wall of the mortice did not tie up with the hole in the tenon, which was drilled slightly nearer the shoulder of the tenon, so that when the peg was driven in for the first time the joint tightened.

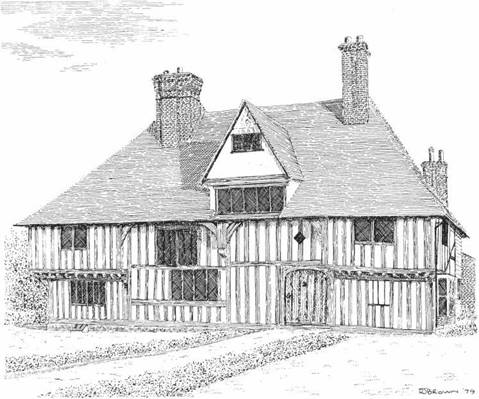

There is evidence that these timbers were not at first permanently fixed during assembling and that plenty of play was left for easy insertion of beams, with the sills and posts not immediately pegged together but temporarily held by means of long wooden pins, shaped rather like tent-pegs, called ‘hook pins’, which could easily be loosened and withdrawn prior to driving in the oak pegs. In most cases all joints were pegged but in some buildings, for instance Synyards, Otham, Kent (11), only the main timbers were secured with pegs, the studs receiving no fixing.

Near the top of some posts, wedge-shaped depressions are to be found, and various views as to their purpose have been put forward. One is that they were used in the process of rearing the frame. Often, however, the position of these depressions is such as to make them impracticable for this purpose and, in any case, if this was normal practice, it would be found on all buildings, which is not the case; even when found, it is rarely on every post. F. W. B. Charles puts forward another explanation in that these depressions were used in conjunction with temporary props to hold the posts in a vertical position whilst the other timbers were assembled. Another and possibly the most likely explanation is that they were used in conjunction

|

11. Synyards, Otham, Kent |

with temporary props to support the structure when repairs were undertaken, perhaps to the sill-beam or when the plinth walls had subsided. Often they appear to have been cut along after the building was constructed. Many, where they have been subsequently protected from the elements by some form of cladding, are still clean and crisply cut, contrasting with the weathered post in which they are to be found.

Timber-framing, whether of box-frame or cruck construction, consists of a system of bays, which are defined by pairs of posts tied together with a tie-beam – to form a cross-frame in the case of box-frame construction, or in cruck construction by a pair of crucks – and which are the points at which the roof loads are collected and transferred to the ground. The bays are connected laterally by wall-plates at eaves level and a sill-beam support on a dwarf brick or stone wall at ground level. Consequently the space between each post or cruck of the

external wall was non-load-bearing and could be of lighter construction. The length of these bays varied considerably from as little as five feet up to between eighteen and twenty feet, determined to some extent by the length of timber available, and formed a close relationship with the overall plan of the building. In a house this relationship is evident enough, the bays corresponding with the desired length of the room, with the short bays generally indicating the position of the cross-passage, smoke bay or chimneystack. Some rooms were of two – bay length, and this is particularly true of the medieval open-hall divided by an open truss, but even then the bays were not necessarily equal in length, the upper bay generally being longer than the other.