louvred, which could be either fixed or adjustable. In some instances the windows were filled in with a lattice of timber slats providing both light and ventilation yet excluding birds. Although the grain could be stored loose or in sacks, it was more common, particularly in the smaller, separate buildings, for it to be stored in bins built of timber and so constructed as to form low partitions. The walls and ceilings were often plastered, presumably to reduce the amount of dust collecting on surfaces, although sometimes, especially where those external walls formed part of the bins, they were boarded. In some areas plastered floors were provided instead of the more usual boarded ones, providing a smoother, cleaner surface which was better for shovelling. Access to the granary was usually by means of timber steps.

Cattle were important to the well-being of the farmer and his family. They kept oxen for haulage, milk cattle for producing milk and consequently butter and cheese, and store cattle for meat. During much of the year they would be kept, except for milking, in the

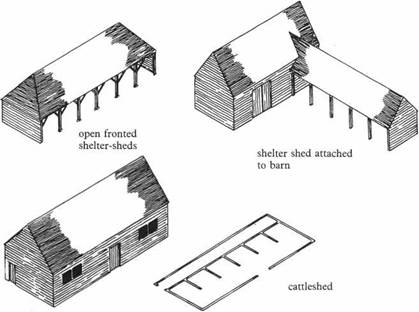

open, but in the winter accommodation, either partially or completely enclosed, was needed. The number of cattle which could be wintered, and consequently the size of the accommodation, depended entirely on the amount of fodder available, and it was not until the eighteenth century, with improved farming techniques producing greater winter feed, that any great numbers of cattle were kept during the winter months.

Enclosed timber-framed cattlesheds are, or at least were, a common enough feature and are mainly of eighteenth and nineteenth century (186). Oak was as always the traditional material, but elm was also popular, as was softwood in the nineteenth century. Like other farm buildings, particularly in the South-East and eastern England, these were generally weatherboarded. The layout and size obviously depended on the number of cattle to be kept and also the provision for feeding and mucking out. Generally the cattle were arranged in double stalls, divided from one another by a low, timber-framed partition and so tethered that they faced a wall or onto a central feeding passage which ran the full length of the shed. The cattle were fed from a manger or loose feeding-box and usually a hay rack. The floor comprised brick paviors or stone slabs sloping down to a wide drainage channel. Until the nineteenth century sheds were low, a hay loft often being provided above, and in many cases the only light and ventilation came from the

|

|