north-west corner was probably the principal solar, the rooms beneath being the buttery, pantry and kitchen linked by the screens-passage to the hall. Further rooms must have stood to the east of the hall but these were undoubtedly remodelled when the parlour and withdrawing-room were built. In the mid-sixteenth century the now unfashionable great hall was sub-divided by the insertion of a floor. At the same time the sleeping accommodation to the east was transformed, and two large bay windows were inserted overlooking the courtyard to light the hall, the new withdrawing-room and the rooms above. This work was carried out in 1559 by Richard Dale. Later in the century the building was further enlarged; a chapel was provided and finally the south wing, with its long gallery which looks like an ‘after-thought’, but there is no structural evidence that the gallery was

|

|

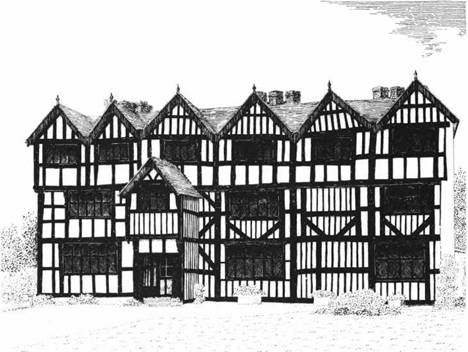

superimposed on an already completed first floor. Other halls also show this continuing development: at Bramall, for instance, the south range with the chapel is of fifteenth-century date while the remainder is late sixteenth or early seventeenth century (the dates 1592, 1599 and formerly 1609 are inside) while at Samlesbury the hall is fifteenth century, with the long south range, except the west end which was added in 1862, built in about 1545.

These houses are famous not only for their external decoration: internally they were often equally elaborate. Needless to say, the great hall received most of the decoration. The spere-truss within the hall developed from the simple draught-excluding device found in the South into an architectural feature elaborately decorated. Undoubtedly the two finest are those at Adlington and Rufford, almost identical, with each of the posts worked in a series of trefoil-headed panels and separated from the adjoining one by a roll-moulding with the posts linked by a four-centred arch formed in two braces. Similar spere – trusses are to be found at Little Morton Hall and Ordsall Hall. At Adlington a battlemented moulded beam, which spans the hall above the dais, provides the springing for the great panelled canopy upon which are displayed the arms of many Cheshire families. While unique in both heraldic display and size, many of the halls of the North-West possess more modest versions of it. The roof structures too received this elaborate detailing. The finest roof is undoubtedly at Old Rufford Hall with its splendid five hammer-beam trusses. The hammer-beams have carved angel figures and the arched braces up to the collar-beam have bosses in their centres. In addition there are three tiers of windbraces forming quatrefoils and in their centre concave-side square paterae. Adlington too has a hammer-beam roof plastered between the purlins with a dormer window on the south side.

Besides these notable examples already mentioned there are other large timber-framed houses of note in the area. In Cheshire, for instance, there is Gawsworth Old Hall, now with 2Vi ranges but originally of three or four. The original planning and function of the remaining rooms are not clear. In Greater Manchester one can cite Baguley Hall, Wythenshawe, the earliest of the great halls of the North-West of early fourteenth-century date. Near Baguley is Wythenshawe Hall, of early sixteenth-century date, while Hall i’t Wood, Bolton, is certainly one of the most attractive of all the timber – framed houses in the North-West. In Shropshire there is Pitchford Hall undoubtedly the most splendid of all the black-and-white buildings in the county. Built by Adam Otley, a wool merchant of Shrewsbury, in about 1560-70, the house is on the E plan but with square projections in the re-entrant angles between the wings and centre. Unlike many of the larger houses further north, the decoration here is obtained only

|

|