bays, each having a projecting bay-window to the two principal upper storeys. The centre two bays were Ireland’s own house, flanked on either side by a single-bay house. Of slightly later date is Rowley’s House (163), equally large but less flamboyant.

In a number of English towns, rows of small houses, each standing on a small plot, were a feature, tending to be long, narrow ranges often sited with their longer sides parallel to the street and only one room deep. At York such development had begun by the fourteenth century at Goodramgate and at St Martin’s Row in Coney Street. The Good – ramgate terrace, known as Lady Row, was built in or shortly after 1316 and originally contained nine or ten houses each consisting of one room, about ten by fifteen feet, on each floor. They are built on the edge of the churchyard, the rents collected from them being used to endow chantries in the church. It is an early example of a continuous jettied range of buildings and, unlike other, slightly later rows of

houses built along and parallel to the street, did not incorporate a small hall open to the roof. At St Martin’s Row, for which a contract survives dated 1335, each house was to have been built with a ground-floor chamber, with an open hearth, with a door and window towards the lane with the chambers jettied over the lane at the front and with a window on the opposite side overlooking the churchyard. The overall length of the row was a hundred feet, and it was eighteen feet wide at one end and fifteen feet at the other. Ranges of identical small houses are a feature of a number of towns, and the existence of these, which often incorporated a shop on the ground floor, implies speculative development for letting. The exceptionally complete range at Spon Street, Coventry, may be taken to illustrate the type that must have been typical in many towns. Each cottage consisted of a ground-floor hall, half of which was open to the roof, with an upper chamber over the other half jettied onto the road and with possibly a cross-passage beneath the chamber from the street entrance to the yard at the back. These houses had recessed-bay open halls with jettied chambers facing the street or a two-storey range facing the street and an open hall behind.

The majority of rural timber-framed houses that survive today are relatively small, and apart from those of manorial status generally belonged originally to yeoman farmers and smallholders. During the latter part of the fifteenth and early part of the sixteenth century, however, a number of timber-framed houses appeared that were much larger than any previously seen, built or enlarged for the gentry who were at that time amassing large country estates. Why these landowners continued to build in the timber-framed tradition when many could undoubtedly have built their houses of the then fashionable brick or stone has never been satisfactorily explained. Without doubt, however, a man could, for the same capital outlay, construct a more commodious house in timber than he could in either brick or stone.

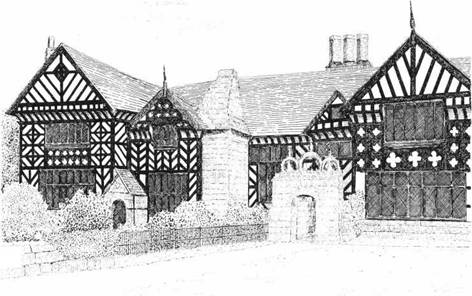

The finest of the houses are to be found in the North-West. The group comprises such notable houses as Rufford Old Hall and Samles – bury Hall, both in Lancashire, Speke Hall, Merseyside (164), Smithills Hall, Bolton, Ordsall Hall, Salford (165) and Bramall Hall, all in Greater Manchester, and Little Morton Hall (166) and Adlington Hall (167) both in Cheshire, all of which have quite rightly long been famous for their size and exuberant decorative framing, with an abundance of Renaissance detailing. The halls in these houses did not differ greatly from those in the rest of England: the usual entrance door led into a screens-passage divided from the hall itself by the spere-truss, as in so many houses in Lancashire and Cheshire. At the

|

|

|

g>^ |