given special decorative treatment, with the struts and windbraces frequently cusped. In the North the roofs were of the king-post construction with little decoration, probably due to the fact that the open hearth was never a feature in northern England and that the firehood, situated at the lower end of the hall, drew the occupants away from the centre of the hall.

In the West Midlands the medieval concept of a cross-wing was retained, as was the spere-truss supported on two spere-posts, an almost standard design in Hereford & Worcester, while in Cheshire and Lancashire it continued to be a feature as late as the beginning of the sixteenth century. The most famous were in the halls at Adlington, Cheshire, Baguley and Ordsall, Greater Manchester, Speke, Merseyside, and Rufford, Lancashire, where they developed from a simple draught-excluding device into an architectural feature elaborately decorated. The open hall in these areas continued to be built long after it had been abandoned in the East and South-East for houses constructed with two storeys throughout.

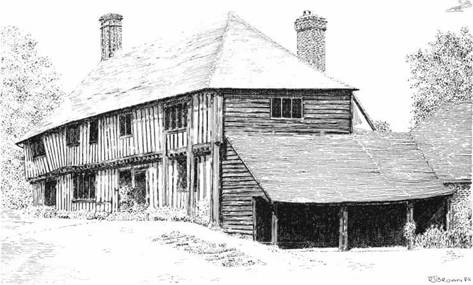

Over much of the highland zone open-hall houses of true and jointed crucks construction are fairly common, often comparing in size with those constructed in the South-East and East, but because of the nature of cruck construction these houses were generally less spacious, with a more limited range of internal design. Some of them were originally single-storey throughout and, from the evidence of the soot-encrusted trusses and rafters, were in some cases divided into rooms by only head-height partitions. A few of these open-cruck halls are of fourteenth-century date – for example, Hill Farm, Chalfont St Peter – but most appear to be fifteenth or early sixteenth century. Although in the West Midlands, and particularly in Hereford & Worcester, these cruck houses still retain their timber-frame, most of the external walls have been rebuilt in stone or brick or have always had stone walls.

Towards the end of the fifteenth century the importance of the open hall as the dominant and principal room in the house began to decline, being replaced by houses constructed with two storeys throughout. The initial impetus came perhaps from the desire for more privacy that the greater number of smaller rooms provided, coupled perhaps with the desire for making better use of the upper storey, rather than from any inconvenience that the open hearth caused. Certainly in many cases the first stage in the modernization of the existing open hall involved the flooring-over of only part of the hall and the retention of the open hearth in the remaining areas forming a smoke bay from the open hearth on the ground floor to the rafters of the roof. Although houses with smoke bays continued to be built as late as the end of the sixteenth century and were not finally abandoned until the end of the seventeenth century, most of the old open halls probably had a chimney, either of timber and plaster or of brick inserted with the entire hall chambered over from the onset.

This change from the open hall to a house of two storeys throughout first occurred in the South-East and eastern England towards the end of the fifteenth century but elsewhere in the country the abandonment of the open hall occurred somewhat later. In the West substantial timber-framed houses, comparable with the largest to be found in the South-East and eastern England, such as Court Farm, Throckmorton, Hereford & Worcester, were still being constructed during the early part of the sixteenth century with an open hall. Even here, however, the open hall had generally been divided horizontally to give an upper floor during the sixteenth century, but it is clear from inventories that many still remained in use in the late seventeenth century. The room over the hall, in many cases because of the low headroom, became

little more than a store and was normally referred to as ‘the chamber over the hall’.

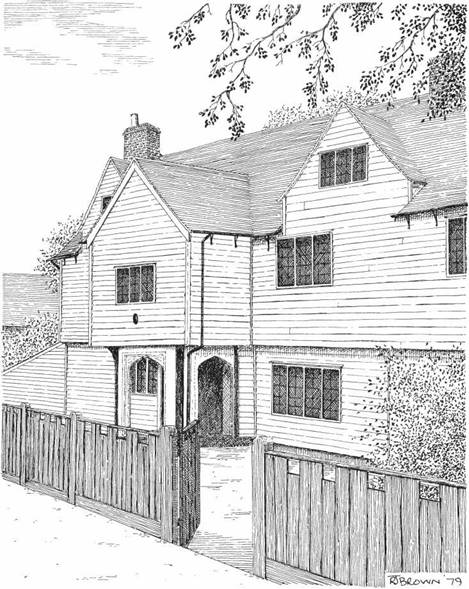

In both the South-East and eastern England by the beginning of the sixteenth century, and elsewhere by the reign of Elizabeth, all but those houses built in remote parts of England and for poor farmers and cottagers were being built with two storeys. Yet two medieval features remained: one was the hall, which still retained its medieval distinction of high and low ends, and the other was the screens-passage. This was no doubt due to the influence the open hall, which was not only an old but also a superior form, had on smaller houses long after it had disappeared in larger houses, and so a screens-passage, still flanked by the impressive ornamented timber screens, was often retained. This was so in many late-medieval houses which had a floor and chimney inserted into the open hall at its upper end away from the screens-passage.

With the abandonment of the open hall the jetties of the cross-wings, which, as we have seen, were a feature of so many medieval houses, could for the first time be extended for the full length of the house. The continuous jettied house (151), as this type is known, was probably the first vernacular timber-framed house type to be built with two

|

|

|

|