Farm, Black Notley, Essex, which may be original. In the halls of the North-West elaborate oriels of five to seven sides were provided, as at Ordsall Hall, Salford, and Rufford Old Hall.

At the other end, the ‘lower end’, the servants and retainers lived. In the open hall the social division between the family and the servants was marked by the central open truss. Even in the smallest house this division between the upper and lower ends is noticeable, with superior architectural details to all those parts not only in but also visible from the upper end.

|

|

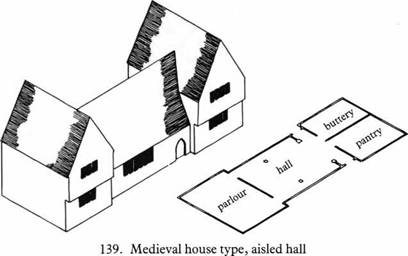

The earliest surviving houses with an open hall are those of aisled construction (139) and are almost certainly of manorial status. These halls, which were larger than those in comparable later houses, had two large bays, approximately equal and each about sixteen feet in length. These aisled houses began as straight ranges of uniform construction under a lofty roof with low eaves. There is evidence, based on Fyfield Hall, Essex, and Old Court Cottage, Limpsfield,

|

|

Surrey, to indicate that a two-bay aisled hall without any other rooms was the simplest type of house; it persisted as late as the end of the thirteenth century.

The first development to this unitary plan was the addition of a further bay, built in series with the hall, at its lower end. This was probably at first a single-storey bay, but early in the fourteenth century, when Stanton’s Farm was built, this service bay was of two storeys. The lower part of the hall therefore contained upwards of five doors – the entrance door, opposite which was usually a back door, together with up to three doors to the service rooms. Consequently there was a considerable amount of ‘coming and going’, and to lessen the draught caused by these doorways the end of the hall was screened off.

Screening was achieved by adding a further bay between the hall and service bay, structurally defined by a spere-truss forming a crosspassage known as the ‘screens-passage’. At first the separation was only partial, with short ‘speres’ or screens projecting from the lateral walls into the hall beside each external door. In aisled construction these screens were formed between the arcade post and the external lateral walls, leaving a wide opening, known as the spere-opening, in the centre leading into the hall. This opening was filled with a curtain or a movable screen. (These movable screens are today rare, surviving only at Place House, Ware, Hertfordshire, a fourteenth-century aisled house, and the later Rufford Old Hall.) The service wing contained on the ground floor the buttery and pantry, each with its own door into the hall, and above these a chamber, probably the ‘solar’, for the private use of the family.

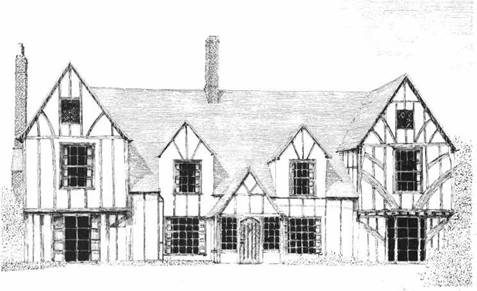

The next development, which occurred in the more important manor houses by the early fourteenth century, was the provision of a bay or cross-wing at both ends of the hall, although the earlier house types certainly persisted alongside it. The earlier examples of these two – storey end bays – late thirteenth and early fourteenth century appear to have been in series, with the hall contained within a larger singlestorey building (Stanton’s Farm, Lampett’s Farm, Fyfield, and Tip – tofts Manor, Wimbish, all in Essex, and Homewood House, Bolney, West Sussex), and it was not until later that cross-wings began to appear in conjunction with halls. In these cases the cross-wings were almost always jettied, as at Baythorne Hall (140), Birdbrook (1360-70), Priory Place, Little Dunmow, and St Clairs Hall, St Osyths, all in Essex.

The lower end adjacent to the entrance still contained on the ground floor the service rooms, while above, the chamber was used according to circumstances, for guests, servants or the adult sons of the family. At the upper end, the ground-floor room was the parlour, used by the

|

£уЗ(2.о^гм |