clay mixed with straw or grass and left to dry but not fired – was sometimes used, as at Ufford Hall, Fressingfield, Suffolk.

In those areas, where the stone could be easily split into thin slabs, these two were used (48E). The studs needed to be spaced close together and have grooves in their side into which the slab could be fitted horizontally, one above the other. In west Yorkshire and sometimes in Lancashire, sandstone flags were used in this way, while in south Yorkshire, C. F. Innocent observed thin slithers of stone, known locally as ‘grey slates’, frequently employed. Similarly, in Coventry sandstone slabs have been discovered in a number of sixteenth-century buildings and still retained at Cheylesmore Manor, while in Stamford, Lincolnshire, slates from nearby Collyweston, usually eight or so inches wide, were also popular. These stones and slates were generally plastered both sides. Oak boards were used in a similar manner, set vertically when the studs were close together (48F), as in the early fourteenth-century granary at Grange Farm, Little Dunmow, Essex, and the late fifteenth-century house by the churchyard at Penshurst, Kent, or horizontally one above the other where the studs were spaced wider apart. Horizontal board infilling was a feature of many timber-framed barns (48G), particularly in the North and West, but few examples still remain for when decayed they

could not be replaced. Some still remain in the upper panels of the timber-framed barn at Home Farm, Hodnet, Shropshire, built in 1619; the lower panels and gables have later brick infilling. In all these forms of construction it would have been necessary for them to be inserted at the same time as the frame was erected and not, like wattle-and-daub, brick-nogging and local stone, inserted afterwards.

External Plastering

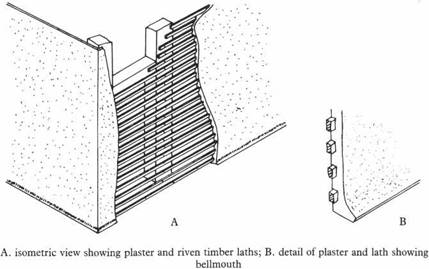

The external plastering of timber-framed buildings began in the sixteenth century and by the latter part of the seventeenth and throughout the eighteenth century had become common practice in eastern England and the South-East, coinciding with the improvement in the quality of plaster and the availability of timber laths (50). Like other cladding materials it was introduced to provide greater comfort for the inhabitants of the buildings.

The consistency of the plaster varied considerably and depended greatly on local traditions and customs. Ideally it was a mixture of slaked lime and coarse sand (normally in the proportion of three to six times the quantity of sand as lime) to which was added a variety of materials: chopped straw, cow-hair, scrapped from the hide, cleaned of dust and finely teased, horse-hair and even feathers were all used to bind the stuff together and increase the strength. In addition road scrapings and fresh cow-dung were often added, and stable urine. One or more of these admixes were introduced into the basic lime-and-sand

|

|