number and shape of the struts. These may comprise king-strutting, twin-angle strutting, curved angle-braces or queen-strutting. Apart from a few decorated examples, particularly in Lancashire, king-post roofs were plain and unpretentious. Generally the posts themselves were sturdy, usually about eight inches or more in section, compared with the more slender crown-post. The height of the posts varied from about five feet up to eight feet, although generally they were somewhere between the two, probably six to seven feet. The top of the posts was often provided with a double jowl to take the principal rafters. Although there are a few timber-framed buildings with king-post trusses in other areas, they are common in the North in medieval and post-medieval buildings and, unlike the crown-post trusses of the South, were widely adopted in the rest of the country in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

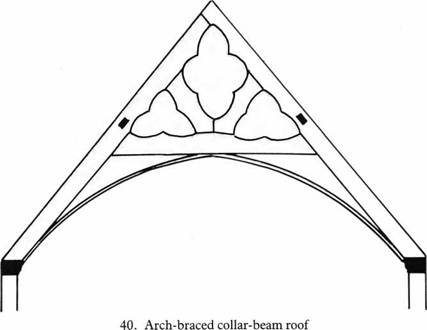

Another, and perhaps the most ornamental open roof used in medieval secular buildings, was the arch-braced collar-beam roof truss (40). In this roof truss the tie-beam was eliminated and a collar-beam

|

|

provided at high level, supported with arch-braces framed either into the underside of the principal rafter and down onto the main post or directly to the main post at the bottom and at the top into the underside of the collar, often so formed to make an impressive Gothic arch. Side purlins, sometimes trenched but more often tenoned into the principal rafters, supported the common rafters. The area above the collar-beam was often filled with tracery. Usually this took the form of bold trefoils or quatrefoils frequently formed by two raking struts between the collar and principal rafters, foiled or finely cusped, and forming, with equally foiled or cusped principals and collar, a decorative panel. In addition the windbraces, of which there may be one or two tiers, were similarly foiled or cusped. Due to the absence of any tie-beams, there was only limited restraint to any overturning movement which in turn tended to cause sheer stresses in the truss-joints, as surviving examples show. The arch-braced collar-beam roof truss was the standard medieval truss for open roofs in western England and may have been influenced by the cruck construction, as suggested by the number of fourteenth-century base crucks with an arch-braced collar. These decorations are to be found in many of the domestic roofs of Hereford & Worcester of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. One of the finest examples is undoubtedly to be seen at Amberley Court, where the main truss is arch-braced with a central quatrefoil and flanking

trefoils, with the intermediate trusses having a higher foiled collar with the rafters cusped below.

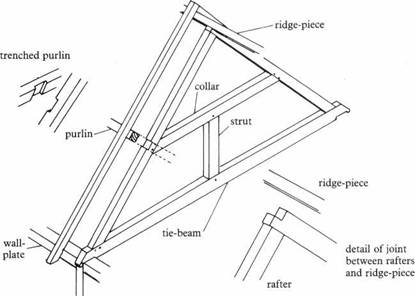

In many ways cruck and king-post roofs were similar in that they both employed ridge-pieces and side purlins laid on or trenched into the crucks or principal rafters. In the West and Midlands during the sixteenth century, when the use of cruck construction began to dwindle, and in the North, when the use of the medieval king-post declined, the trusses that succeeded them continued to adopt this same trenched or through purlin technique (41). With this type of roof the principal rafters are of a much larger scantling and in a lower plane than the common rafters, with the purlins trenched into their upper face onto which the common rafters sit. Also, more often than not, the roof incorporated a ridge-piece, a feature not normally employed in the clasp – and butt-purlin roofs of the South-East and East.

In all forms of roof construction, with the exception of cruck and arch-braced, the trusses are built off a tie-beam, preventing any outward movement of the principal rafters. However, there were buildings in which the tie-beam was often in an inconvenient position. To overcome this problem, several methods were adopted. One was to eliminate the central part of the tie-beam, the end being framed into a post which rose from the main cross-beam at floor level to the underside of the principal rafter or collar-beam. This system was

|

41. Through or trenched purlin roofs |

generally adopted in trenched-purlin roofs. In clasped – or butt-purlin roofs a similar method was used, but the post was replaced by a diagonal member, introduced from the main post to the principal rafter, into which the remaining length of the tie-beam was framed. Finally there was the use of upper crucks which rose from first-floor cross-beam level but which did not always continue to the ridge, being held together by a collar.

From the seventeenth century onwards the development of the double-pile house provided the carpenter with another problem to overcome. With the increased depth of these houses and when the roof covering required a steep pitch, the resultant roof would have been of excessive height. To overcome this, two identical roofs were placed side by side to form an ‘M’ roof with a valley gutter between. The disadvantage of this roof type was that it divided the roof space into two, needing two separate accesses, both small with little headroom. A roof was, however, devised in which the valley wall was raised and the purlin forming the valley was supported on a tie-beam strutted off ceiling beams. The result was to provide a single attic with reasonable headroom over much of its area.

From the eighteenth century imported softwood replaced oak as the predominant timber used in roof construction and marked the end of traditional roof carpentry. Carpentry techniques became progressively simpler, with nails, bolts and metal straps often replacing the elaborate joints formerly employed based on the many contemporary pattern books which became available during the eighteenth century. The trusses used were often adaptations of old ones; the king-post truss, found almost exclusively in northern England up to the seventeenth century, was adopted in many parts of the country and can be found in many of the timber-framed farm buildings erected with softwood in the nineteenth century in lowland England.