Roof Types

The roof of any building, and of a timber-framed one more perhaps than others, is archaeologically the most important feature, for it is generally the least altered part. There are a considerable variety of roof types (35), and R. A. Cordingley in his British Historical Roof Types and their Members: A Classification divides them into eight major groups subdivided into seventy-five classifications which are again subdivided to make nearly eight hundred variants, although some have only minor differences. Many of these roof types are, however, unsuited to timber-framed buildings. Essentially two types of roofs were used in timber-framed construction: single-framed roofs, which consist entirely of transverse members such as rafters, which are not tied together longitudinally, the weight of the roof being transferred equally along the external wall frame, and double-framed roofs, in which ridge beams and purlins are employed, transferring most of the roof load onto trusses which are supported on principal wall-posts.

The simplest and earliest forms of single-rafter roofs have no longitudinal members above the wall-plate, the pairs of common rafters, spaced between one and two feet apart, meeting at the apex of the roof and held apart and gaining its longitudinal stiffening solely by the roof-coverings. Slightly more elaborate are the close-coupled rafter – roof types in which the pairs of common rafters are tied together at their base by a tie-beam, and the collar-rafter roof, in which the common rafters are secured at mid-point by a horizontal collar – beam.

All these ties prevented the feet of the common rafters from splaying out, causing the roof to collapse, but there was still a degree of instability. To remedy this, the passing-brace roof was designed, and to provide lateral stability long, slender timbers running parallel to the rafters were engaged by means of halved-lapped joints to all the horizontal and vertical members they passed. This method, commonly employed on aisled construction, was a typical feature of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Also used at this time was scissor-bracing in which the pairs of rafters were linked by braces crossing one another in their passage in the centre line of the roof. In aisled construction both passing-braces and scissor-bracing were often used in the same building, as at Purton Green Farm, Stansfield, Suffolk. Needless to say, these single-rafter roofs were still subject to structural failure, mainly from racking, in which the common rafters, although being kept parallel by the roof-battens, incline from the vertical. To overcome this, in the thirteenth century diagonal bracing, fitted into trenches cut into the outer faces of common rafters, often formed into a saltire-cross, was fitted between each bay. The single-rafter roof form was one generally used in most timber-framed buildings in the twelfth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

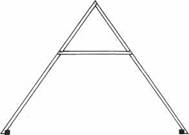

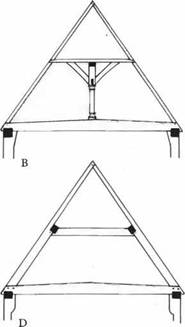

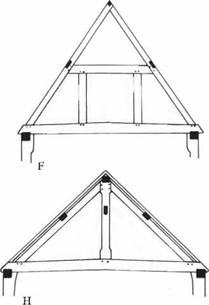

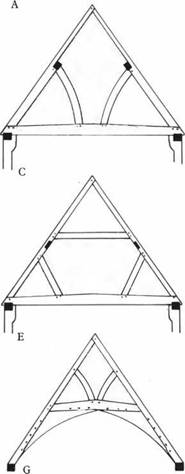

A. single-framed; B. crown-post; C. & D. clasped-purlin; E. butt-purlin; F. through or trenched purlin; G. arch-braced collar-beam; H. king-post

and thirteenth centuries but seems unlikely to have persisted, in other than poor buildings long since disappeared, after about 1400.

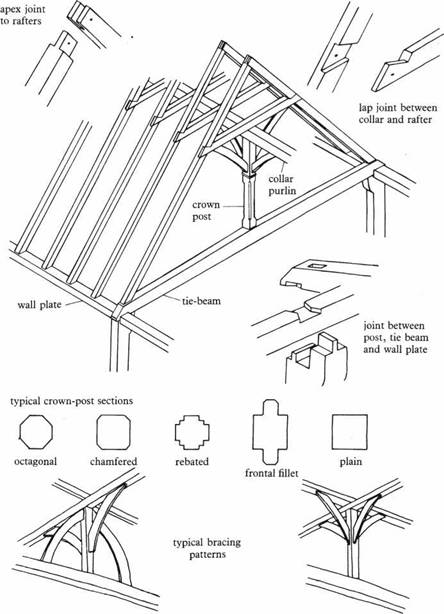

To overcome the longitudinal collapse of rafters, a collar-purlin was introduced (36), running the whole length of the building and placed immediately below the collars and supported along its length at each bay division by crown-posts and at its end by a king-stud. The crown-post or king-stud is framed into a tie-beam at the bottom and the collar-purlin at the top, thus supporting the collars along its entire length and so the pairs of common rafters and hence the roof load. The collar-purlin was rarely fixed to the collars but restrained by friction, therefore removing any tendency for the longitudinal collapse of the rafters. The crown-posts too required braces to prevent lateral movement, while longitudinal braces were added to triangulate the roof.

It is the arrangement of these braces and the size and shape of the crown-post itself that are the main variants of crown-post/collar-purlin roof construction. The most common form of bracing was that in which the crown-post was braced four ways at head, twice to the collar-purlin and to either side of the collar. Others were braced only at the head longitudinally to the collar-purlin, while others had in addition braces at the bottom between crown-post and tie-beam. The most important braces were at the head of the crown-posts, for they prevented the sideways movement of the collar-purlin as well as providing longitudinal stability by triangulating the roof structure. Yet there are crown-posts which are braced only at the foot of the tie-beam, and others with no bracing whatsoever, a feature of Berkshire and Wiltshire. In some instances the crown-post is carried up beyond the collar-purlin to the apex of the roof, as a king-post. At Tiptofts Manor, Wimbish, Essex, the crown-posts appear to have been intended as king-posts but they are truncated and fail to reach the rafters’ apex. Braces were generally curved but straight ones were also used, although they became less common in later years.

There is an almost infinite variety of crown-post designs, varying in length of shaft as well as shape and decoration. The length can vary from as little as a foot to seven feet or more depending on the span, pitch and collar-beam height. Generally, however, they were between five and six feet high. In many houses built before the middle of the fourteenth century they were either square in cross section or chamfered to form an octagonal shaft. Bases and caps were rare, although those that were chamfered did produce a simplified base and cap when the chamfer was stopped. Later, in most houses, particularly in the central open trusses of the halls or solar chambers, the crown-posts were decorated, with the cap and base moulded and the post itself shaped, usually octagonal in section, but chamfered, rebated and

|

|