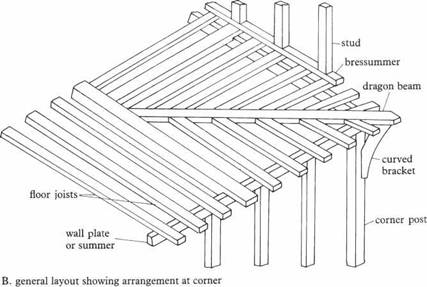

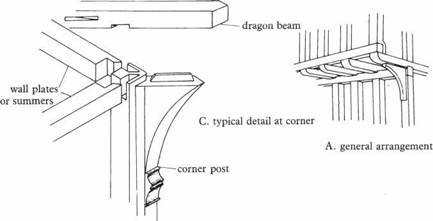

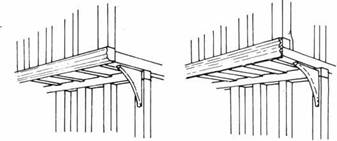

(The word comes from the French jete, meaning something thrown out.) Jettying can occur on one or more sides and even on occasion on all four sides and on more than one storey, projecting in some cases as much as four feet. When jettying was to one side only, the construction was simple, for all that was required was for the floor joist to cantilever over the wall below and rest on the ‘summer’, the beam situated at the back of the overhang (29). When the overhang was on two adjacent sides, the process was a little more complex (29B). It was necessary to change the direction of the floor joists, and to enable this to be undertaken one of the floor joists was replaced by a larger one to which was framed another horizontal beam, called the ‘dragon-beam’, which ran diagonally to the corner of the floor. Into this beam the ends of the floor joists were framed, each pair set at right-angles, although sometimes the last few were framed at a slight angle. Towards its end the dragon-beam was supported by and framed into a massive corner or dragon-post, usually finely carved, which often had a curved bracket to support the outer end of the dragon-beam. The best area to see these carved dragon-posts is undoubtedly East Anglia. Some excellent examples can be seen at the Moyses Hall Museum at Bury St Edmunds, but many examples can be seen in situ – for instance, a house in Northgate Street, Ipswich.

To support the jetty along its length, additional curved brackets, occasionally carved and springing from moulded shafts, were sometimes provided framed to the studs and floor joists. Scrolled console – brackets were also frequently used, however, as these were cut from a solid piece of timber as distinct from a curved timber which were

|

|

|

29. Jetty construction – 1 |

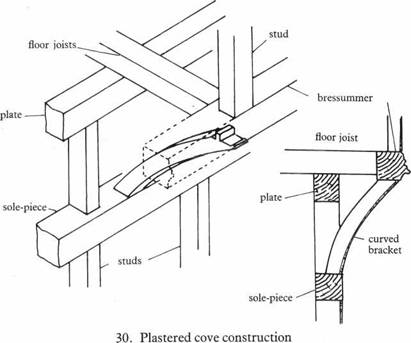

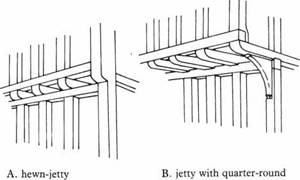

generally weaker. This weakness was perhaps realized, for by the middle of the seventeenth century they were occasionally banded with iron. On many of the timber-framed houses of northern England a plastered cove was constructed below the projection (30). A rare feature is the ‘hewn-jetty’ in which the end post extends the full height of the building with the lower part – the ground floor – being reduced in width to form the jetty (31A). Although this eased the jointing problem

|

|

at this point, the jetty provided was of a very limited projection, rarely more than a few inches.

Once the floor joists were in position, the framing of the next storey could continue, with a bressummer laid along their ends. In some instances, and this is particularly true of some utilitarian buildings, the ends of the projecting floor joists were left square, as at the Hanseatic Warehouse, King’s Lynn, Norfolk, but generally the ends were shaped into a quarter-round and left exposed (31B). In some buildings the ends of the timbers were framed into the bressummer rather than supporting it from beneath (31C). This was a popular feature from the sixteenth century onwards. An alternative method used in concealing the ends of the floor joists, also popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was to provide a fascia (31D). Both fascias and bressummers were either moulded or richly carved. Fascias are today rare, for once decayed they were not replaced. An excellent carved example still survives at the house previously mentioned in Northgate Street, Ipswich.

Jettying was first introduced in the thirteenth century – Tiptofts Manor, Wimbish, Essex, being of this date – and remained popular until the latter part of the sixteenth century, when its use began to decline, although it still continued to be used in the seventeenth

|

end to joists |

|

|

C. jetty with joists framed to D. jetty with ends of joists

bressummer concealed by fascia