joints from the fourteenth century onwards included the soffit tenon, structurally the best of all the types, often with diminished haunches above the tenon to prevent winding. This was also achieved by housing the shoulders in various ways. Generally those of the seventeenth century, although having additional features, were structurally inferior, and by the beginning of the eighteenth century floor joists were commonly slotted into position – cogging – which was both quick and easy.

Generally the bridging-beams spanned between bays with the joists spanning between them and the front or rear wall. Medieval floor joists were heavy timbers, about eight inches by five inches deep, and were laid on their side (that is, with broad side horizontal), and it was not until the sixteenth century that they gradually began to be reduced in size, perhaps to five inches by four, while at the same time being

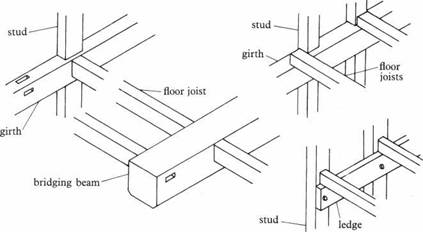

spaced further apart. It was not, however, until the beginning of the seventeenth century that the practice of placing floor joists on their broad side was universally superseded by the improved carpentry technique of placing them on their narrow sides. This led to the introduction of floors with beams and joists of the same depth designed for the then fashionable plastered ceilings which could then be uninterrupted by the beams. The ends of the joists either sat on or more commonly framed into the girth; on poorer-quality buildings they sat on a ledge pegged to the inside of the frame. The bridging-beams, however, were almost always tenoned, sometimes double-tenoned for extra strength, into the girth of the cross-frame or external wall. This was not always the case, for the floor in the fourteenth-century cross-wing at Baythorne Hall, Birdbrook, Essex, is supported on four samson posts placed in the side walls, so relieving the walls of the weight of the floors.

Bridging-beams, the largest timbers (rarely less than twelve inches square) in any building, always acquired some form of decoration. The plain chamfer was the basis of many of these mouldings, but during the seventeenth century the ovolo moulding with many varieties of stopped ends became popular. In high-quality timber-framed buildings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries there are sometimes two parallel bridging beams to each bay, sometimes with heavy transverse beams to form a square pattern to give a coffered ceiling. These beams were usually richly carved or moulded (27).

One of the outstanding features of some timber-framed buildings is jettying – the projection of an upper storey beyond the one below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

H |

|

|

А., В. & C. moulded beams fifteenth and sixteenth-century date; D. late sixteenth – early seventeenth century; E. mid-seventeenth century; F. early seventeenth century; G. late sixteenth – early seventeenth century; H. seventeenth – early eighteenth century.

26. Ceiling beams – mouldings

|

|