Andrew Ballantyne Merlin

In legal terminology, a ‘misprision’ is a theft – the taking of something without permission. In the essays that follow, buildings have been taken up without the permission of their designers, and have been made to mean things that their designers did not have in mind. The first of these thefts was the most literal – the actual removal of a monumental building from one kingdom to another: Stonehenge was forcibly removed from Ireland and re-erected on Salisbury Plain as a memorial to the British dead. That is what Geoffrey of Monmouth tells us in his account of 1136.1 What happened was that the British king, Aurelius, was going round his kingdom repairing damage done by the Saxons. He restored York, and went on to Winchester, from where he visited a monastery near Salisbury, where there were buried the bodies of the princes and leaders who had been betrayed to the Saxons. Aurelius wanted to erect a special memorial to these distinguished men, and he was advised that the person to provide him with what he wanted was the prophet Merlin. It was good advice. Merlin knew of just the thing. It was the ring of stones on Mount Killaraus in Ireland, which were much more impressive than anything that modern craftsmen could devise. When he was questioned as to why the stones had to be brought from Ireland, and local ones could not be substituted, he explained that the stones had been brought from deepest Africa, and had magical medicinal properties. The Irish tried to stop the British from taking

the stones away, but the British army overcame the Irish one and the stones were taken away. At first it was impossible to move the huge stones, but then Merlin devised apparatus that made it possible to take them down, load them on to ships, and reassemble them near Salisbury in exactly the same configuration as before.

|

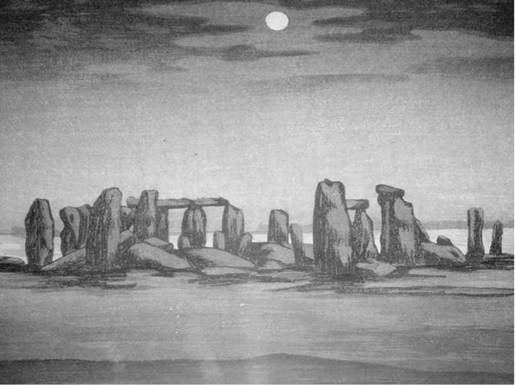

1.1 Stonehenge in a twentieth-century Japanese print. One culture through the eyes of another |

Along with the physical relocation here, there was a cultural relocation. Whatever the stones may have meant to the Irish, they were certainly not a memorial to the British dead, which was what they became once they had moved. Along with the physical theft, which is unique to this example, there is the cultural seizing of the object, and that is what all the examples in this book have in common. They have all been taken up and put to a use that their designers did not foresee. It is this cultural relocation that is of real interest, not least because we no longer believe Geoffrey’s story, which is too fantastical to be considered as proper ‘history’ by today’s standards. Even in his own day, not everyone believed him. Polydore Vergil, for example, said that Geoffrey’s account was impudent lying, designed to promote the British at the expense of the Romans and Macedonians.2 What we can do, is to read the story for what it tells us about Geoffrey and his times, although there is

the curious fact that this story of translocation does address one of the perennial questions about Stonehenge: where did the stones come from? They are not local stone, and are much harder than the chalk of the plain. It has been a more recent supposition that the stones might have been brought from Wales – itself an arduous and extraordinary task, but one that twentieth – century archaeologists have entertained.3 There is also a current idea that the stones might have been deposited by the movement of glaciers, which we might find plausible now, but such ideas were not available in earlier ages. Whatever the answer, it is plain that there is a question there to be answered, and Geoffrey’s tall story certainly addressed that question, without making it quite explicit that the question had been raised. When Merlin’s deed is placed against others in Geoffrey’s historical record, the date for the structure’s arrival near Salisbury would be about ad 485, about 650 years older than the chronicle, which he completed in 1136.

By that time the Norman invasion of 1066 had put an end to the rule of the Saxon kings, whom Geoffrey treated as barbarian interlopers. The British had been driven west by the Saxons, to Wales and Cornwall, but also some of them had been living all along in Britanny, which was also ruled by the Normans. Curiously, in Geoffrey’s world the stretch of water that divided Bretagne (Britanny) from the island Grande Bretagne (Britain) was less culturally significant than the cultural divide between the Britons and the Saxons. There is a way here of seeing that Geoffrey might be hoping to see the old British ways being restored by the Normans, as the Saxon influence waned. More importantly, though, there is a very telling assumption about buildings and place that underlies the story, that is no less strongly there for the fact that Geoffrey himself takes it as read and feels no need to make comment on it. There is no feeling that the building must be made from the indigenous rock. Just as the British and Saxon populations can move about and withdraw from the land, so there is a possibility of moving a building from one place to another by force of arms, and having it as a national monument. It is difficult to say what Geoffrey would have meant when he said that the rocks had come from Africa – a place that was remote from him, and unknown to him except as a token of the exotic. Certainly there is no suggestion that one would want to see Stonehenge as an exotic African presence on Salisbury Plain – on the contrary, it seems that once the stones had been brought to Ireland, they were legitimately Irish, and once they had been won from the Irish – by force – they became entirely and irrevocably British. There is something quite cosmopolitan about the attitude – the people and objects are not bonded to the place by ties of blood and tradition, but can move and be annexed. Also, there is a comment about the arrangement of the stones: Merlin ‘put the stones up in a circle round the sepulchre, in exactly the same

way as they had been arranged on Mount Killaraus in Ireland, thus proving that his artistry was worth more than any brute strength’.4 This makes the point that the change in meaning occurred without there being any material change to the shape or disposition of the stones, only in their location. Plainly the idea of ‘originality’ was entirely alien to Geoffrey’s conception of artistic accomplishment. There was some originality involved in devising the mechanisms by which the stones could be moved, but that sort of ingenuity could be substituted by brute strength, if enough of it were available. Merlin’s taste and judgement were to be applauded in his ability to arrange the stones without any originality whatsoever, in exactly the same disposition as they had occupied in Ireland.

Geoffrey of Monmouth was certainly wrong in saying that Stonehenge was built as a funeral monument, as there is no evidence of appropriate burials here, but he and his contemporaries did not know that, and the conjecture seemed plausible enough. One of the things that is unusual about Stonehenge is that it is so very enigmatic. We have no direct account of what its builders thought they were building, what their intentions were, or whether or not they succeeded. We know very little about them. Most of what we know about them is that they built Stonehenge, and we can see that it was a monument that took a great deal of effort from people who had only primitive tools at their disposal. Therefore, it must have been important work and it must have been well organized and sustained, which suggests a degree of order and prosperity in the society, as its people were certainly able to do more than simply subsist. Nevertheless Stonehenge itself is the most substantial piece of evidence that supports these conjectures, so that while we can see what subsequent ages have made of Stonehenge, we cannot compare these suppositions directly with the building’s original programme. In this sense all that we can know of Stonehenge are its various misprisions in the hands of various authors who have brought their own cultural apparatus to bear on the monument, and through it have refracted what they have seen. When Geoffrey of Monmouth tries to tell us about Stonehenge, he tells us something about the monument and, rather more certainly, something about himself and the culture in which he operated.