enden and Rolvenden, both in Kent, Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire, Drinkstone, a typical west Suffolk mill, Friston and Framsden, both in Suffolk, Reigate Heath, Surrey, and in Sussex those at Clayton, Argos Hill, Hogg Hill, Icklesham and Cross-in-Hand.

The construction of the postmill varied little in principle from other timber-framed buildings but greatly in detail. Oak was the principal timber used, although in Sussex pitch pine was a popular alternative

|

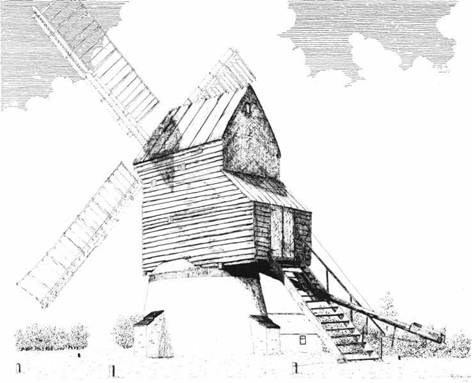

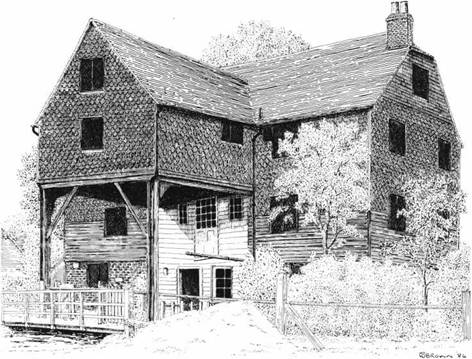

196. Cat and Fiddle Mill, Dale Abbey, Derbyshire |

(Clayton and Argos Hill). The body of a postmill is carried and pivoted on a massive central post called the ‘main post’, about which the body of the mill revolves. Supporting the main post in its vertical position are four raking ‘quarterbars’, each morticed and tenoned into the main post at one end and generally framed at the other end to the ‘crosstrees’ by means of a birds-mouth joint and iron straps. The main post is quartered over the crosstrees but is not supported by them, being kept an inch or two above. Those crosstrees were first laid directly on or more commonly buried beneath the surface of the ground to give the mill greater stability. Later they were raised on brick piers but not fixed to them. Most postmills were constructed with two crosstrees set at right-angles to each other, but a few mills had three crosstrees and six quarterbars. These were at Chinnor and Stokenchurch, both in Oxfordshire, Bledlow Ridge, Buckinghamshire, Costock, Nottinghamshire, and Moreton, Essex. All of these have now either collapsed or been demolished.

The top of the post terminates either with a ‘pintle’, turned out of the solid, or an iron gudgeon or ‘Sampson head’, a cap and bearing of iron. Pivoting and rotating on top of this is a great transverse beam, called the ‘crowntree’, on which the weight of the body of the mill rests. The framing varies greatly: generally on each end of the crowntree, are fixed the ‘side girths’ which are jointed and pegged to the four corner posts, and about these timbers the mill is formed. The top and bottom side girths, at the eaves and the lower ground floor, run parallel to the side girths, and between these are vertical studs with diagonal bracings. At the breast and tail, cross timbers, called ‘the breast’ and ‘tail beams’, are secured to the top side girts to carry the neck and tail bearings of the windshaft respectively. In addition the breast beam is supported in its centre by a vertical member, called the ‘prick-post’. The breast beam is sometimes curved, while others are splayed to form an obtuse angle at the centre. Two large horizontal timbers, called ‘sheers’, are fixed either side of the main post, the full length of the body and beneath the lower floor, to support the mill about the post. Beneath these is a ‘collar’ or ‘girdle’ – a heavy wooden frame around the main-post – which steadies the mill in rough weather, relieving the strain from the main-post. Occasionally other methods have been used to steady the mill: at Sprowston Mill, Norwich, a ball-bearing collar was used, and this is now at the Bridewell Museum, Norwich. At Argos Hill a vertical iron track is fitted around the main-post with iron rollers on brackets fixed to the underside of the lower floor.

Early mills had a simple pitched roof, as at Bourn, but later curved rafters were generally used to accommodate the larger brake wheel. At Cromer Mill, which dates from about 1720, an ogee roof can be seen, the rafters shaped to follow a reverse curve to a point at the ridge. The whole of the framing is usually covered by horizontal shiplap boarding either painted white or tarred, but some postmills in Yorkshire were covered with vertical boarding, while in Sussex mills were occasionally partly or almost completely covered with flat galvanized iron sheets painted white. This can still be seen – for instance, the mills at Argos Hill and Clayton are clad on the breast only, while the mill at Cross-in-Hand has the breast and sides clad. To make the mill waterproof, the boarding to the breast is extended beyond the sides, with the sides and the roof carried beyond the rear boarding. A number of mills had the weatherboard to the breast carried down below the lower floor in a shield-like extension, as at Chillenden Mill, to give protection to the mill’s substructure. Some mills had the weatherboarding lath-and-plastered inside to keep the interior dry and free from draughts. At Aythorpe Roding, the interior of the roof, with part of the walls of the floor below, was similarly treated.

Access to the mill body is gained by means of a wide ladder from the ground up to the platform at the rear of the lower floor. Above this ladder many mills had a porch canopy over the door, and this varied greatly from mill to mill. Some had a simple lean-to (Great Chishill, Cambridgeshire), some a pitched roof, some a flat curve, while others were bonnet-shaped. Some postmills had balconies at the rear, as at Holton, Suffolk, and a few even had galleries around the eaves.

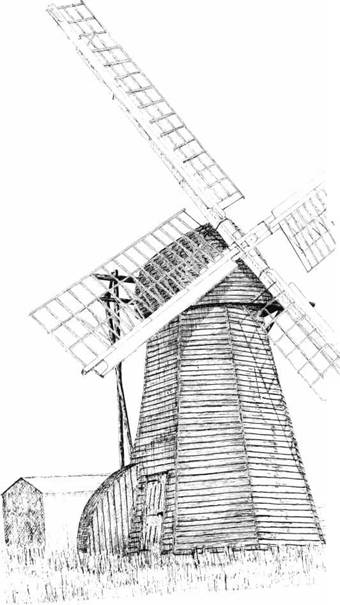

The early postmills were the open-trestle type, and these can still be seen (Nutley, Great Chishill, Bourn and Chillenden, are good examples) but in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries roundhouses were added to many mills to give protection to the substructure and to provide extra storage space. These roundhouses are not attached to the mill in any way, the main-post passing through an opening at the apex of the roof. Later, many mills in east Suffolk had the roundhouse built at the same time as the mill itself, and some had as many as three floors and were as high as the body of the mill proper. Mills were sometimes raised when the roundhouse was constructed, and the mill at Saxtead Green (197) was raised three times altogether, the last time probably in 1854. The roundhouse at Holton has two floors, one of which is below ground level. The walls are generally built of brick, stone or flint, but in Sussex timber walls were sometimes used. The roofs are now always boarded and felted, but a few had tiles (as can still be seen at Stevington Mill), slates and even thatch. The weatherboarding of the mill body is generally extended down and shaped to clear the roof of the roundhouse. Some mills had a small petticoat, attached to the underside of the lower floor of the mill, to protect the opening in the roof of the roundhouse. Occasionally the roundhouse has no roof, and in this case the petticoat is built out to form the top of the roundhouse as at Kibworth Harcourt. Two doors were provided, on opposite sides of the roundhouse, so that access could be obtained wherever the sails were positioned.

In the Midland-type postmill the roundhouse roof is attached to the body of the mill with support gained by timbers set at right-angles to the sheers, called ‘outriggers’. Cast-iron rollers are fitted to the ends of the sheers and outriggers which run on a curb on top of the roundhouse wall. This arrangement can be seen at Cat and Fiddle Mill, Dale Abbey, probably built in 1788 (a date carved on the crosstree) and Danzey Green mill.

Tower mills were a logical development from the postmills. They consisted of a fixed tower with a timber cap which contained the windshaft with the cap being the only part which turned to face the wind. The tower was built of brick, stone or timber, those of timber being clad with weatherboarding and known as ‘smock mills’ because of their likeness to the linen smock that was once the traditional dress

|

|

of the British countryman. Generally smock mills are octagonal in shape but six, ten and twelve-sided smocks have been constructed. Most smock mills are on a brick base which varies from a few courses high, as at Stelling Minnis, Kent, to one, two or even three floors.

The main structural framing of a smock mill has large timber ‘cant’ posts at each corner, which extended for the full height converging to give the body of the mill its batter. These cant posts are secured to timber sill-plates on top of the brick base. The inherent weakness is that it was difficult to provide satisfactory fixing between the cant post and the sill and there was a natural tendency for the feet of the cant posts to move outwards, allowing the structure to collapse. The cant posts could be either secured with iron straps bolted to oak blocks on the inside of the sills, or mounted on iron shoes bolted to the sill. At the top, the cant posts are framed into the timber track or curb on which the cap rotates. Between and housed to each cant post are horizontal ledges, with a vertical central post fixed between these, strengthened with diagonal braces and filled in with vertical studs to ensure a strong and stable structure. Two large beams, called ‘binders’, carrying each floor are partly framed into the cant post and rest on the horizontal ledges. These binders are arranged at right – angles to those of the floor above, so spreading the load around the mill.

Smock mills are generally covered by horizontal weatherboarding, although in Cambridgeshire vertical boarding was sometimes used and can still be seen at the derelict mills at Swaffham Prior and Sawtry. The corners were always vulnerable, and to overcome this problem the alternate horizontal boards to each side are extended over the adjoining boards of the other side. These corners were often protected by lead or zinc to make them weatherproof. The boarding of the smock mill, like that of the postmill, is either tarred or painted white.

The taller smock mills have a stage, usually fixed to the brick base at the first floor or the meal floor, enabling the miller to load up the grist waggon or regulate the sails with ease. These stages are generally of wood, supported by brackets built out from the brick base, but for the odd stage, usually in Kent (for instance, Stelling Minnis), vertical uprights are provided. Two doors were provided onto the stage, opposite each other, so access could be obtained no matter where the sails were positioned, and this also applied to the doors on the ground floor whether the mill had a stage or not. The smock mill varied greatly in size, from several floors, as at Cranbrook, Kent, to a few floors, as at West Wratting, Cambridgeshire.

There are still a number of smock mills surviving today in Kent, where brick towers were never as popular as elsewhere. The finest in the county is undoubtedly Union Mill, Cranbrook, which dominates

the skyline of the town. It was built in 1814, is now owned by Kent County Council and is open to the public. Others of note in the county are Herne Mill, built in 1789, Draper’s Mill, Margate, built in the 1840s, Meopham Mill, built in 1801 (from, it is said, an old broken-up battleship from Chatham), Stelling Minnis, built as late as 1866, and West Kingsdown Mill, built at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Other smock mills of note are those at Lacey Green, Buckinghamshire, the oldest surviving one in the country, reported to have been built in 1650, West Wratting, Cambridgeshire, with the date 1726 on the brake wheel, Upminster, London Borough of Havering, dated on the beam below the fantail as 1799, Dalham Mill and Great Thurlow, both in Suffolk, and in Sussex those at Chailey, built in about 1830 and moved to the present site in 1864, Blackdown Mill, Punnetts Town, Rottingdean and, the finest in the county, the one at Shipley (198) built in 1879. All these mills are preserved, some still in working order, and most open to the public on certain days.

Most mills were generally used for grinding corn or other cereals, or on occasions snuff, pepper, mustard and vegetable oil, but there were also a number whose function was the drainage of land, generally in the Fens and the Broads. Those used to drain the Fens were usually smock mills, with the exception of the small mill at Wicken Fen, Cambridgeshire, have now largely disappeared. The mills of the Broads are far more numerous, being generally of bricks. These often replaced earlier smock mills, the only one of these to survive is at Herringfleet, Suffolk (199), built in 1830, its survival undoubtedly due to the fact that it belonged to the Somerleyton Estate which kept it working until 1956 when the county council agreed in principle to its preservation. Another but much smaller mill owned and worked by the Somerleyton Estate until 1957 stands nearby, at St Olaves, Norfolk. Built in 1910, it is the only surviving smock drainage mill with patent sails and fantail.

Other types of mills were used; the composite mill was a combination of a postmill and tower mill. The mill had the body of a postmill with the post removed, and was mounted on a short tower, in the same way as a cap, which ran on casters or tram-wheels with the whole body turned into the wind by a tail pole or a fantail mounted on the roof. There were only a few of these mills built and, with the exception of the one built at Monk Soham, Suffolk, they were all adaptations: the only advantage seems to have been that of economy – using a sound body of a postmill rather than having it demolished.

An unusual design was the hollow postmill, a Dutch invention, which was first used for drainage. It had a small post-mill-type body, which contained the windshaft, brake wheel and wallower, and an upright shaft which passed down through a hollow post to drive the

|

|

|

|

machinery below. Only a few of these mills were built in England, the most famous being the mill at Wimbledon Common built as a hollow postmill in 1817 but later rebuilt as a composite.

A variation was the small, skeleton, hollow postmill often used for drainage in the Fens and the Norfolk Broads. These windpumps were skeleton framed, winded by a large weather vane and driving the pump, by common sails, through a crank in the windshaft.

Unlike those constructed of brick or stone which have no distinctive architectural or structural style apart from the ‘Lucan’ (the protective loading gantry, a feature of most water-mills), those constructed of timber and clad with weatherboarding and often crowned by a red tiled roof are features of many of the riverside towns and villages in the South-East and eastern England. Like the windmill, they were an important feature in the structure of the medieval village, but although many stand on sites where mills have stood since the Domesday Survey was made, the majority that survive today date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some being built as late as the nineteenth century.

Oak was the traditional material used for the construction of watermills, although towards the end of the eighteenth century softwood was the timber often employed. A feature of many mills is the use, long after it had been abandoned in domestic buildings, of the gambrel or mansard roofs which provided additional space for the housing of corn bins and other equipment. The frame was almost always clad with horizontal weatherboarding, although in parts of Cambridgeshire vertical boarding was the traditional covering and can still be seen at the watermill at Lode. Generally the boarding was painted white, although presumably at one time there was a fashion for blue colour work, which may account for the number of ‘blue’ mills about. In many instances sides and back were often tarred but in most cases even here the front was painted white. Occasionally one finds a mill which is clad not in timber but in tiles, the most famous being Shalford Mill, Surrey (200).

Water-mills varied greatly, not only in size but in the method by which the water drove the wheel. The various types can be identified by the position at which the water strikes the wheel. An undershot mill is turned by water flowing through the floats at the bottom of the wheel first, while with an overshot wheel the water strikes the top first. An overshot wheel – usually placed on a man-made or natural weir – is the more expensive but far more efficient of the two, needing only around a quarter of the volume of water to produce the same amount of power. Some mills are built across their streams with internal

|

|