split door. From the middle of the nineteenth century onwards more importance was given to the housing of cattle, and legislation, particularly that of 1885 and 1926, laid down that more hygienic accommodation was to be provided, with more windows and ventilation. In addition, as hay was at this time only part of the winter diet, the cattleshed became open to the roof, the hay being kept in stacks or hay barns.

Another method of housing cattle, and one commonly employed, was the open shelter opening up onto a foldyard. Foldyards became a feature from the late eighteenth century onwards with the increasing number of cattle being kept over winter. In many cases young heifers and bullocks could be kept in the open the whole year, although they could not necessarily be left in the open fields where they would damage the pasture for the coming spring and summer. The answer was to house them in a yard providing some shelter and where food and water could easily be provided.

Open-fronted shelter-sheds or ‘hovels’ were provided in these foldyards, giving additional protection to the cattle during the worst of the winter and providing a place where the cattle could be fed and watered by means of mangers and hay racks as usual. These shelter-sheds provided a cheap and satisfactory way of housing young cattle and were particularly common in eastern England and the South-East, where rainfall was relatively low. The structures were simple: the roof was carried above the open front on timber posts generally built on a stone or brick foundation, the frame to the end and rear walls being usually weatherboarded. Unlike the cattleshed, there were no stalls and no means of tethering the animals. The form of these timber-framed shelter-sheds appears to be almost completely standardized since the eighteenth century with very little difference in the lengths of the bays or their construction. The number of bays actually varied considerably, from three up to as many as eight, although four or five appear to be most common. In most cases there was one row nearly always forming part of an enclosed or partially enclosed yard, frequently being built at right-angles to and attached to the barn.

Although foldyards and shelter-sheds were generally located in the farmstead, this was not always so. In parts of the South-East, particularly on the Downs, timber-framed, weatherboarded outfarms were provided, generally comprising a barn for the storage of hay, a foldyard with a shelter-shed or cattleshed and perhaps a stable. Most date from the nineteenth century, when they were recommended because of the saving in transport and time.

Stables

Unlike the cramped, ill-lit cattlesheds of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the stable was a more spacious, better lit and ventilated building. This was due undoubtedly to the importance given to the horse, an expensive animal to buy, rear and feed. In construction timber-framed stables are similar to the cattleshed, generally being constructed with an oak frame and generally weatherboarded, although some are infilled with wattle and daub or brick-nogging. The majority date from between the late seventeenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century, after which most were constructed of brick, although some are obviously earlier, perhaps of late sixteenth – or early seventeenth-century date.

Most of these timber-framed stables generally housed between three and five horses and incorporated a harness room and perhaps a loose – box. Each horse was given an individual stall (divided by a stout, high, timber stall partition) with a manger and hay rack. The floors, like those of the cattlesheds, had to be impermeable and were of stone, or of brick paviors specially designed to give a good grip to the horses hoofs. In many instances a loft was provided over the stable either for the storage of corn or more commonly for the storage of hay.

Cartsheds

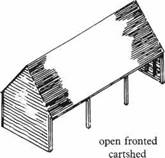

Prior to the nineteenth century farm equipment comprised mainly carts, waggons, ploughs and harrows, and on most farms some form of shelter was provided to protect these items which were usually made of wood with only the moving parts of iron (187).

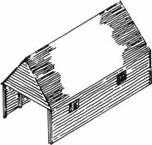

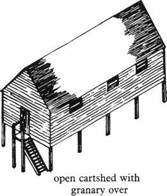

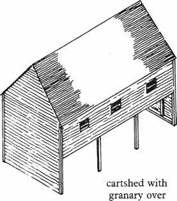

The most common form of timber-framed cartshed was an open – fronted building, resembling in many ways the open-fronted shelters for cattle, with the front supported on timber posts and the sides and rear usually clad with weatherboarding. Internally there was no division between the bays, enabling easy access to all the equipment. The length of these cartsheds varied greatly from a single bay to over ten, although generally they were four or five bays long. Most cartsheds were open along their long side but some, particularly those of a later date, were entered from one or both ends, those opening at both ends permitting easier access for the carts and waggons, enabling them to be pulled in one side and out the other. Generally these cartsheds were single-storey but it was not uncommon to provide a loft above, usually for use as a granary. In these cases it was not uncommon for the ground floor to be completely open, as at Peper Harow, providing excellent ventilation to the produce stored above but giving only limited protection from driving rain or snow to the equipment below.

|

|

|

open ended cartshed |

|

|

|

|